Journey of Light at Town Field Park: What It Meant to Make a Memory Field in Public

In late September 2025, during the momentous year marking the 50th commemoration of the end of the war in Vietnam and the beginning of the Vietnamese and Southeast Asian diaspora, I watched Dorchester's Town Field Park change, not through construction or a ribbon cutting, but through presence. Journey of Light: A 1975 Memory Field arrived quietly and then began to speak, not in captions or grand statements, but in motion, shadow, wind, and the way people gathered beneath it. For weeks, the park held a field of suspended nón lá, conical hats that many of us carry in our bodies as much as we carry them in our memories. What I did not fully expect was how quickly the installation stopped being “an artwork” and became a place.

I have been asked a lot about the conical hats, the nón lá. Some people assume the answer is purely cultural, a recognizable symbol, a way to signal Vietnamese identity at a distance. That is part of it, but it is not the center. For me, the nón lá is not decoration. It is labor, lineage, protection, and a kind of quiet dignity. It is the shape of people who have always had to move through the world with both softness and strength. When I suspended the hats in the air, I was thinking about migration and memory, but I was also thinking about the unspoken. The things we hold above our heads to keep going. The things we learn to carry without ever naming.

1975 is not just a year. It is a threshold. It is the beginning of so many “after” stories for Vietnamese and Southeast Asian families, including my own. It is grief and survival braided together. It is a rupture that keeps echoing across generations. I wanted to create something that did not force a single narrative, because our community is not one story. We are many stories, sometimes harmonious, sometimes in tension, sometimes still forming. A memory field felt like the right container, a place where meaning could emerge without being prescribed.

Mockup by Emily Cedeno

Town Field Park has long been a gathering place in Dorchester, and it is also the proposed home for the long-term memorial I am building with our community, 1975: A Vietnamese Diaspora Memorial. Installing Journey of Light there was not just aesthetic. It was relationship-building. With the land, with the neighborhood, with the City, and most importantly, with the people who live around the park and carry the histories this work is trying to honor. I wanted to see what happens when Vietnamese memory is not kept private, not contained to our homes, our ceremonies, or our anniversaries, but given room to breathe in a shared civic space.

And something happened. Elders came and stood beneath the hats for a long time, sometimes without speaking. Families came back with relatives. Youth showed up with curiosity, asking questions that felt both simple and profound. People who did not know the backstory still felt the atmosphere shift, like the park had been softened and charged at the same time. The most moving moments were often the smallest, an auntie pointing upward and explaining something quietly to a child, a passerby slowing down mid-walk, someone returning days later and saying, “I brought my mother. I wanted her to see this.”

Photo by Lee-Daniel Tran

As an artist, I think often about what public art is actually responsible for. It is easy to say public art should spark dialogue, but I am more interested in what it makes possible. Does it make room for us to feel? Does it make space for people who have been erased to be present without apology? Does it offer a way to hold complexity without rushing to resolve it? Journey of Light taught me that when an artwork is rooted in community and treated with visible care, people respond with trust. They allow themselves to enter. They bring others in. They begin to treat the space as shared.

It also reminded me that the work is never only the artwork. What the public sees is the final breath of something that has been held, carried, solved, lifted, and cared for again and again behind the scenes. There were planning meetings, safety considerations, site walks, weather worries, last-minute adjustments, and the steady coordination it takes to work on public land. There was the physical labor too, hands sorting and preparing materials, hands lifting, securing, checking tension, checking pathways, checking every detail that keeps the installation both beautiful and safe. Volunteers showed up with their time and their bodies, doing the unglamorous work that rarely gets named, and technical partners brought the expertise that turned an idea into something structurally sound and truly possible. It was a labor of love in the most literal sense, love measured in hours, in care, in problem-solving, in showing up even when it was hard.

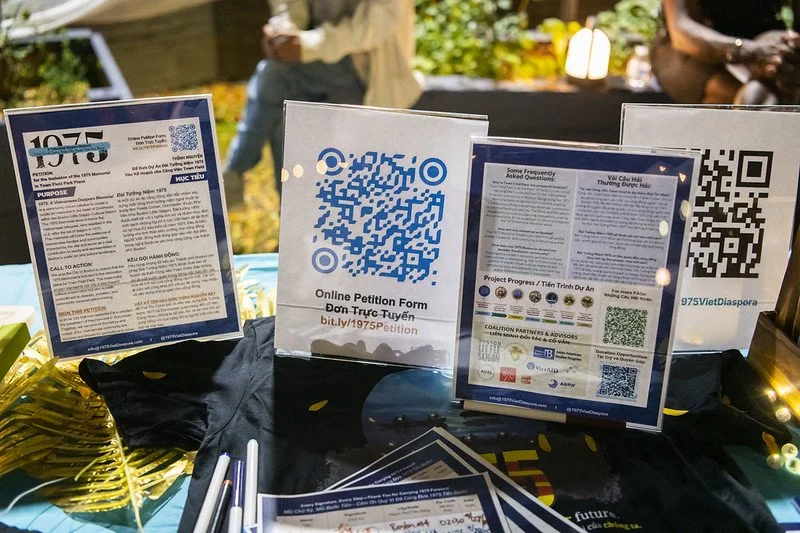

I want to name this clearly because so much community-based work is made to look seamless, and that invisibility can be harmful. The truth is, it takes a team. It takes partners. It takes resources. It takes people who believe that our stories are worth building infrastructure around. I am deeply grateful for the support of the City of Boston’s Un-monument initiative and the Mayor’s Office of Arts and Culture, and for all the collaborators, volunteers, and community partners who helped bring this installation to fruition. Support like this does not just fund materials. It funds possibilities. It signals that public memory can be reimagined, that monuments do not have to be rigid, heroic, or singular. They can be living, temporary at first, iterative, shaped by community presence, and built over time with accountability.

If there is one insight I carry forward most strongly, it is this, our community is ready. Ready for more gathering, more storytelling, more places in the city where we can recognize ourselves and one another. Ready for a memorial that does not freeze us in the past, but honors how we have moved, survived, built, and loved in the aftermath of 1975. Ready for public space to hold our complexity. The long-term memorial at Town Field Park is still a journey. Public land brings long timelines, City processes, and real constraints, and we are moving through them with patience and persistence. But Journey of Light gave us something vital. It gave us proof that the park can hold this work and that the community wants it there. It gave us a shared experience we can point to, not as a finished statement, but as a beginning.

If you are someone who visited, shared a story, brought a loved one, or simply paused for a moment beneath the hats, thank you. You were part of the artwork. You were part of what made it real. If you are new to my work, welcome. I hope you’ll stay close as we continue building toward the permanent memorial, and as we keep creating spaces for intergenerational connection and healing in Dorchester and beyond. If you want to support this work, there are many ways. Share the story. Bring someone into the conversation. Partner with us. Contribute resources if you have them. Advocate for culturally grounded public art in Boston Little Saigon and across the city. This is not just about one installation. It is about what we decide belongs in public, and who gets to shape that belonging.

Photo by Mina Kim

I am holding a lot of gratitude and a steady commitment as we move forward. Journey of Light was a memory field, but it was also a signal. We are here. We have always been here. And we deserve a civic landscape that remembers us with care.